Last weekend we were busy with the pretty nymphs in the mountains of Kamrup. The location is about 20km to the south of Boko in the Kamrup district of Assam. It was a gobsmacking phenomenon, a spectacular sight to behold.

I heard about it a long time ago — the mass emergence of a species of periodical cicadas along the Boko Chiring, near Gohalkona village and the nearby jungles along the borders between the Kamrup district of Assam and the Ri Bhoi district of Meghalaya. They emerge from the ground in broods every four years, and to be precise, every leap year. So we love calling them Leap Year Cicadas. This year they started coming out by the third week of April, coinciding with the weather forecast, “heavy rain is coming soon.” But most of them are still underground, waiting for the rains to come.

We wanted to see the cicadas molting with our own eyes. Daring the ongoing heatwave, three of us — Emmanuel Bolwari, Dr. Bilnang K Sangma, and I — started from Tura around 9:12 in the morning of April 27. We stopped at A·chik Dhaba of Rajapara for lunch. Conversation with the dhaba manager helped us learn more about the cicada sites.

We reached Rangsapara village around 2 in the afternoon. Our support team was waiting there. We had a discussion with our guide, Lenon Koksi — destination Boko Chiring. We took along plenty of cooked rice, gal·da na·kam and wak jo·krapa, all packed in banana leaves.

We reached Gohalkona village around 5 in the evening. Quite a lot of people were already there, ready for the hills. The local Garo people called this species of cicada Chenggari. We heard the people talking about “Chenggari Oka,” which literally means “drawing out the chenggari.” Why should they draw out the cicadas? The answer is, to eat. I grew up eating the roasted green cicada of the Dundubia genus. Even the adult green cicada has a soft exoskeleton, but the exoskeleton of the leap year cicada is different. The body of a fully sclerotized adult is no more soft as that of the green cicada. So, the gatherers collect the teneral cicada in its molting stage or draw it out.

It was like participating in a festival! Some going on foot, some by motorcycles and pickups. The cicada gatherers of all ages, including boys and girls, gather themselves in their own groups before sunset. A gatherer’s gear includes the indispensable container and a good torch. Some go solo, some in groups. And there are people like us — with a different purpose. Their mission is to pick as many tender cicadas as they can.

“Not much in Boko Chiring yet,” we were told. So we followed other gatherers southwards. Ascending the rising hill a few miles, our driver was reluctant to drive further off-road. Leaving the car on the roadside, we walked further south-east for about 5 kilometres. It was getting dark, we saw a high mountain on the right side, illuminated by hundreds of torches. A kilometre further, we met a kind couple on a motorcycle, known to our guide. “It’s almost Mawdangop village,” they told us. They led us to a rising hill on the left side of the small road.

We crossed a small stream called Bita Chiring and entered a bamboo grove. We heard the cicadas buzzing! We were welcomed by a cool misty spray coming down from above. “So, this is cicada rain!” we said to one another. Hundreds or thousands of cicadas on bamboos and trees, and the ground was moist with their peeing. Cicadas cannot eat solid food, their mouths have no chewing parts. They live off by sucking fluid from plants. They let off the excess liquid by peeing.

There we saw the cicada nymphs coming out of the ground. These cicadas follow the cycle of four years. They live underground for four years as immature nymphs, feeding off the sap of the roots of plants. Then the nymphs come out in broods, start molting and become fully grown adults after some hours, ready to mate.

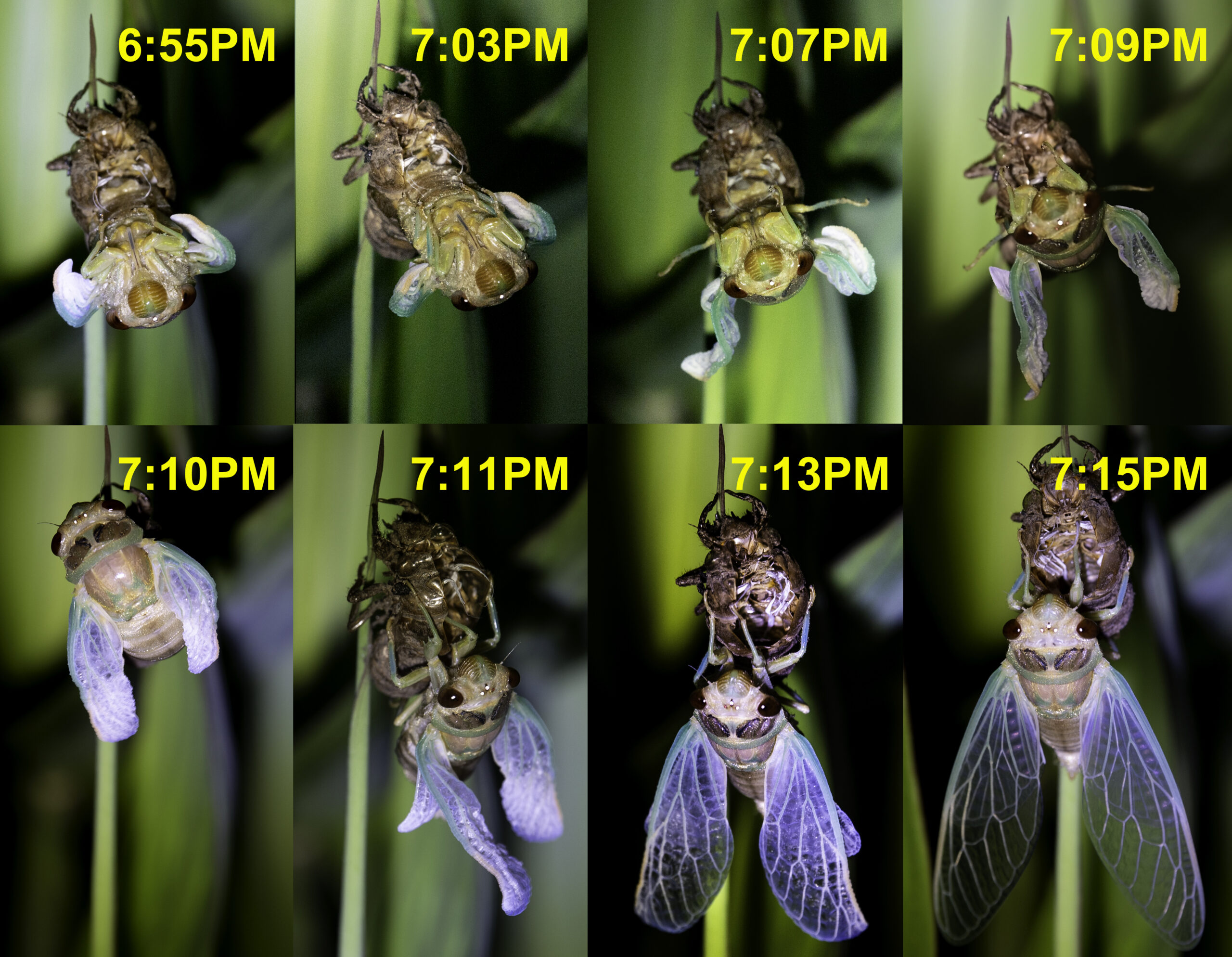

The emerged nymph looks for something upright, climbs it a foot or two, and securing itself there, the molting process begins. It waste no time to molt. Molting starts with length-wise breaking of the nymph’s mesothorax. The adult-to-be cicada gradually pushes itself out of the shell. After about an hour it is fully outside, clinging to its discarded nymphal exoskeleton. But some took longer than an hour, and we saw one or two unable to complete the process of molting — they get stuck!

We were busy admiring the cicadas. 9PM, one of us heard the sound of thunder; rain was imminent. We packed our things, tracked the way back to the road. We could not find the way back, thus reaching a steep rocky wall along the stream. We managed to descend the rocks and reached the stream just below the road to Mawdangop village.

No thunder, no rain — the sound was from the aeroplanes flying in different directions. There we sat down beside a clear shallow pool on a black rock, with lots of shrimps and etchaluk ronggros, unmindful of our presence. Not much hungry, we had our dinner there, on the table of flat stones, for the food bearer was becoming unfriendly with the weight he was carrying. The cicadas were not invited to dinner, yet many came because of the light from our torches.

Coming back we met a group of about twenty people on the way, all cicada gatherers. “They’re coming all the way from Gohalkona, so 5km is nothing. My legs aren’t tired at all,” quiped one of us. Yes, nobody was tired. We reached our car after 10 PM. Somebody had written on the dusty rear windshield, “Sani gari? I love you 2.” Plain water could not wash it off; “she” must have used an oily or acidic fruit to write it. Making half a circle through Gohalkona, Kompaduli, Hahim we reached our base camp at Aradonga around 11 PM. We plunged into the cool Dilsing river to refresh ourselves and spent the night at the office premises of Immanuel Church.

Sunday, April 28: A beautiful blazing day — people going to church in their Sunday bests. We went to Rangsapara for lunch. The Koksi family prepared a variety of Garo traditional dishes for us, the numero uno being chenggari jo·a.

4PM — Pastor Sanden K Sangma arranged motorcycles for us. Destination Nowapara, we took the Kompaduli-Langpih road. It was a high climb, the cool mountain air brushing against us. We stopped at 25.83571, 91.21773, asked for directions, and continued left from the main road. We didn’t know exactly where the cicadas were emerging, we had to find the gatherers. It was getting dark, Emmanuel and I stopped behind to photograph a beautiful cicada (pic below).

The mountain road is ideal for motorcycle rallies, invigorating air but leaving a dusty trail. Riding further north-east, we saw our team’s motorcycles parked at 25.85149, 91.23303. Beyond the reach of cellular network, a murmuring brook welcomed us to the nature slashed and burnt. This brook, Dron Chiring, is deep between the two hills face to face. Following the road and the brook along the valley would have led us to the village of Dolatawa, and then to the route we took the previous evening. I believe it to be a part of what the Garos called Rong·toturi A·bri (hill). The place is a jhum field. A little investigation revealed a bamboo grove as its previous vegetation.

We saw many cicada nymphs emerging and molting. Jhum field, the place is devoid of trees. We observed this the night before — those fully grown adult cicadas do not fly right away, instead they climb up a nearby tree. Here, we found many adult cicadas crawling astray on the ground. So, despite the presence of many adult cicadas there was no cicada rain. We spent there more than 3 hours watching them, photographing and enjoying the mobile-free calmness. Most of the cicada nymphs are still underground, waiting for rain. We’ll go back, for sure, after a shower or two.

Look at the photos above. After discarding the nymphal exoskeleton, the teneral cicada starts to slowly unfold its crumpled wings. When a winged insect eclose into an adult it pumps hemolymph into its wings. The photos below show this process.

The cicada as seen in the pic above ultimately turns black as seen in the pic below.

Only a few periodical cicada species are known in the world. They are special. Wouldn’t it be wise to protect atleast one emerging site as their sanctuary without human interference? It’s amusing to think of a Chenggari Festival every four years at Gohalkona or Hahim.

About the periodical cicadas

There are more than 3000 species of cicadas. The periodical cicadas are special. They are called periodical because the cicadas of such a species follow a certain cycle in emerging from the ground. I know, from scientific literature, only 9 periodical cicadas worldwide, excluding the periodical cicadas under discussion. The 7 species belong to the genus Magicicada of eastern North America. The other 2 species are the Raiateana knowlesi (8 years cycle) of Fiji and the recently discovered Chremistica ribhoi (4 years cycle) of the Ri Bhoi district in Meghalaya, India.

The 7 species of the genus Magicicada of the North America follow the 13 year cycle and the 17 year cycle: one brood emerging every 13 years, and the another every 17 years. 2024 is a signigicant year, for those two broods will be emerging at the same time this year — tomorrow or next week, cicada enthusiasts are waiting for them. According to research, those two broods haven’t emerge together since 1803.

The Chremistica ribhoi found in the Ri Bhoi district of Meghalaya come out every 4 years, coinciding with FIFA World Cup, hence the name World Cup Cicada! It was a recent discovery, and the species has been classified as Chremistica ribhoi by the zoologists. The periodical cicada of Gohalkona hill and its adjoining areas also come out every 4 years, but always coinciding with leap year. I haven’t found any scientific literature on the Leap Year Cicadas. The Leap Year Cicada, to us the laymen, looks identical to (or the same as) the World Cup Cicada. Is it the same species? Or a sub-species? We wait for the answer from the zoologists.

Namen poraie suk ong•jok